Today I’m moving source code (mainly python) from the genomes subversion repository over to a new repository on BitBucket.

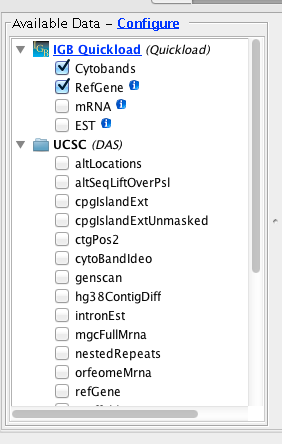

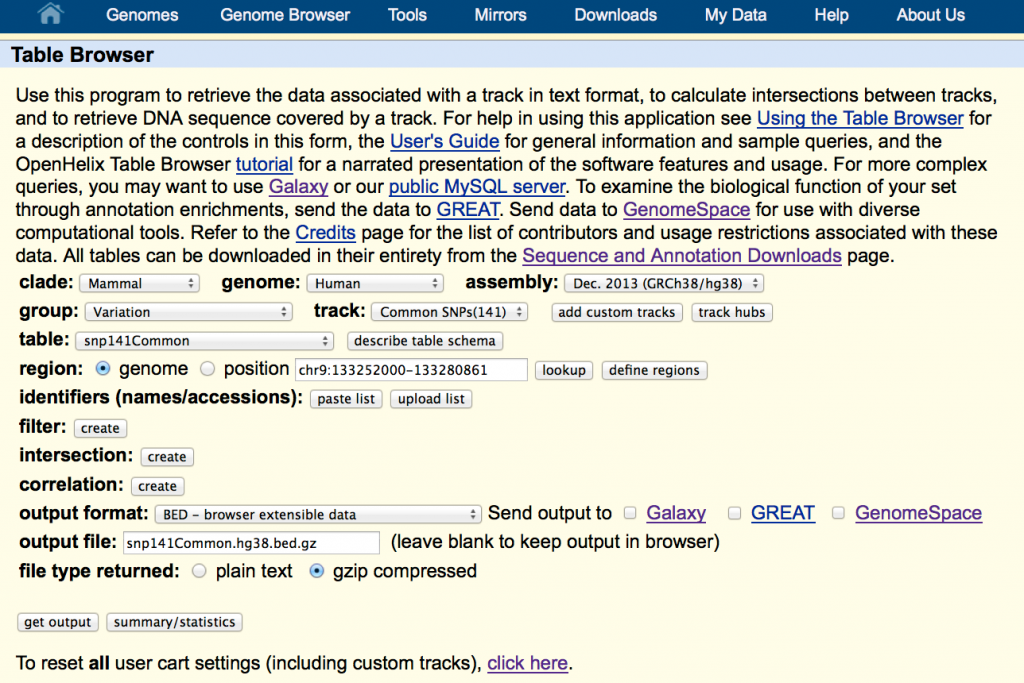

The genomes subversion repository contains version-control data files for many different genomes that we’ve collected from many sources, such as the UCSC Genome downloads page, the UCSC Table Browser, Phytozome (for plants), and model organism databases like DictyBase. We launched the genomes repository back in 2008 as part of an Arabidospis 2010 project grant that support IGB from 2008 to 2012. Our original idea was to use version control systems (cvs or svn) to track big data files from Arabidopsis and other species. The repository would not only serve as a useful data archive, it would also provide a way to feed data into IGB.

However, the genomes repo also contains source code we wrote for converting data files, setting up QuickLoad sites, and other tasks. The source code was stored in a directory named “src” (for “source”). You can browse it here: https://svn.transvar.org/repos/genomes/trunk/pub/src/.

Today, I’m moving all that source code over to a new repo hosted on BitBucket: https://bitbucket.org/lorainelab/genomes_src.

I’m doing this because the BitBucket UI for browsing code, reviewing changes, and managing the project is about a thousand times better than what we are currently using on our subversion server. Since BitBucket offers free source code hosting for reasonably sized repositories, there’s no point in hosting any of our source code ourselves, and during the last year, I’ve been happily migrating all our lab code onto BitBucket. Also, I’d like to start using git for version control, at least for all our source code. Setting up a git repository on our server would probably not be difficult, but then we would have yet another service to maintain. Rather than try to host everything we do on our own machines (which consume electricity and sysadmin time) I’ve realized we should off-load as much as we can onto public, free resources like BitBucket. And at least for now, BitBucket seems like the best option because it’s run by Atlassian, which seems like it has staying power, a mature management structure, and excellent support.

More about the genomes repository:

The genomes repo contains a lot of data, not just code. In fact, most of is data – more than 11 Gb worth of sequence files, annotation files, and some meta-data files describing what’s there.

I’d love to migrate the data onto BitBucket and start using git and not svn for managing the data. I’d love to make it possible for people to fork the repo, improve the annotations, and then issue pull requests back to the main site. The problem is: I don’t know if BitBucket can handle a repository as big as ours – it’s 11 Gb. Also, most of our files are in binary formats (2bit, .tbi, .gz, etc) and I’m not sure how git will handle those files when I or other people make a change. Will it store multiple copies of an enormous file if I modify a small part of it? How would diffs work? It would be terrific if git could somehow handle our binary formats in a smart way.

So for now, I’ll continue to use our subversion server to host and version control the data sets, but I’ll use bitbucket for source code, which is probably what the team at Atlassian would prefer.

One last comment: For now, I’m leaving the “src” directory untouched in the original genomes repo, but I’ll add a notice letting users know that this part of the repository is moving to bitbucket.