In spring of 2015, Mason and I visited Dr. Scott Shaeffer’s genetics class at Lenoir-Rhyne University in Hickory, North Carolina.

The goal of our visit was was to teach students about genomics and genetics using Integrated Genome Browser. We also hoped to gain fresh insight into how new users respond to the IGB interface.

Lecture on genes and development.

To start, I gave a talk on developmental genetics, describing how a single mutation in a gene can have huge consequences for a developing embryo. I explained how advances in technology have made sequencing genomes more affordable than ever, allowing researchers to quickly identify disease causing mutations.

Hands on training with IGB.

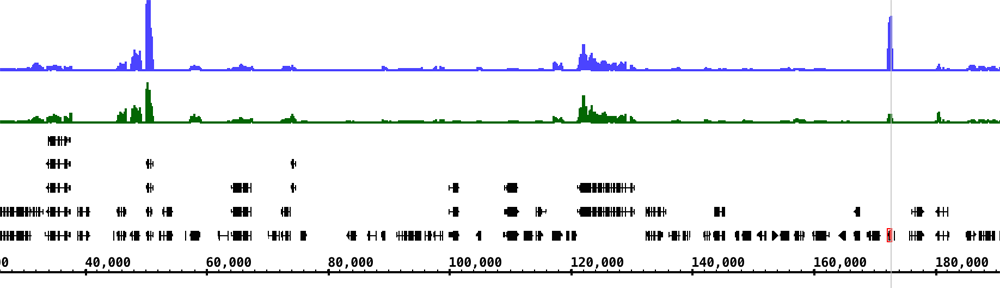

Students then worked hands-on with genomic data using IGB. Their first task was to find genetic mutations by exploring whole genome sequencing data. They then used the data to build coverage graphs, allowing them to find deletions. The final task was to explore my own personal 23andMe data using IGB to see if I was at risk for any genetic diseases.

After a quick demonstration, the students had no trouble visualizing the data in IGB. Also, we were happy to see that no-one had any trouble installing IGB on their personal laptops.

Mason and Dr. Schaefer answering questions.

This was the second time the IGB team has visited Lenoir-Rhyne. In 2013, Alyssa Gulledge visited another of Dr. Schaeffer’s classes, which was using IGB to annotate the newly assembled blueberry genome. At the time Mason was still attending school there, and this visit was his first exposure to genome visualization tools. IGB really stuck in Mason’s mind, and after graduating he joined the Loraine Lab as an intern, eventually taking over the role of lead tester on the IGB project.

We hope that this year’s visit will inspire other students to pursue careers in science and technology.

We hope everyone had fun learning about developmental genetics and IGB.